Understanding Chernobyl Lesson

Voices From Chernobyl: Survivors' Stories from NPR

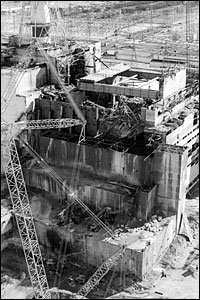

Twenty years ago this month, a routine maintenance test at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in northern Ukraine veered wildly out of control. At 1:23 in the morning on April 26, 1986, there was a disastrous chain reaction in the core of reactor No.4. A power surge ruptured the uranium fuel rods, while a steam explosion created a huge fireball that blew the roof off the reactor. The resulting radioactive plume blanketed the nearby city of Pripyat. The cloud moved on to the north and west, contaminating land in neighboring Belarus, then moved across Eastern Europe and over Scandinavia. From the Soviets: utter silence. There was no word from the Kremlin that the worst nuclear accident in history was under way. Then monitoring stations in Scandinavia began reporting abnormally high levels of radioactivity. Finally, nearly three days after the explosion, the Soviet news agency TASS issued a brief statement acknowledging that an accident had occurred.The memories of survivors were collected for the 10th anniversary of the disaster in the book Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of the Nuclear Disasterby Svetlana Alexievich. We hear some of their stories: those living with illness and fear, and those sent in to clean up the mess and monitor the damage.

|

This is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED from NPR News. I'm Robert Siegel.

Unidentified Man#1: An accident has occurred at the Chernobyl atomic power plant as one of the atomic reactors was damaged. Measures are being taken to eliminate the consequences of the accident. Aid is being given to those affected, a government commission has been set up. Mark Boardman: Soviet officials are now calling the Chernobyl nuclear plant accident a disaster. SEIGEL: Michael McIvor: Western nuclear experts are saying it is the worst nuclear plant disaster in history. And that there are... We're going to hear now the memories of some of those who survived Chernobyl. Those living with illness and fear. Those sent in to clean up the mess and monitor the damage. Their stories were collected for the 10th Chernobyl anniversary in the book Voices From Chernobyl, The Oral History of the Nuclear Disaster by Svetlana Alexievich. We'll be hearing their stories in translation, read by actors. First, a woman who lived in Pripyat closest to the reactor. The city was built to house the plant's workers and their families. Fifty thousand people lived there. Here's what Nadjiesda Vigovskya(ph) remembered. SEIGEL: People came from all around in their cars and their bikes to have a look. We didn't know that death could be so beautiful. Later the evacuation zone was expanded. In all more than 100,000 people were uprooted in Ukraine and neighboring Belarus. Nadjiev DeBorakova(ph) lived in the village of Kweniki(ph) in Belarus, which had some of the highest levels of contamination. Here's a reading of her memories of that time. SEIGEL: I had crazy thoughts. Where should we go? Maybe we should kill ourselves so as not to suffer. This was just in the first days. Everyone started imagining horrible diseases, unimaginable diseases. And I'm a doctor. I can only guess at what other people were thinking. Now I look at my kids, wherever they go they'll feel like strangers. My daughter spent a summer at pioneer camp, the other kids were afraid to touch her. She's a Chernobyl rabbit, she glows in the dark. They made her go into the yard at night so they could see if she was glowing. |

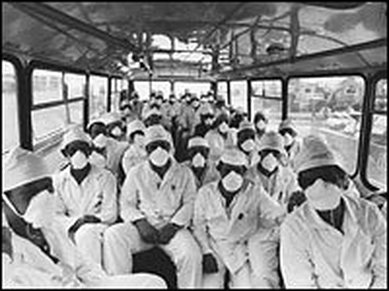

A month after the explosion, Chernobyl employees head off by bus to work in a highly contaminated environment.

|

While the evacuation was going on, firefighters were furiously trying to put out the fires. They burned for 10 days. More than 30 people died from the direct effect of the fire and acute radiation poisoning. Terrible deaths. The widow of a fireman who was killed told her story. Her name is Ludmila Ignachenko(ph).

SEIGEL: At the morgue they said, want to see what we'll dress him in? I do. They dressed him up in formal wear with a service cap. They couldn't get shoes on him because his feet had swelled up. They had to cut up the formal wear, too, because they couldn't get it on him, there wasn't a whole body to put it on. It was all wounds. The last two days in the hospital I'd lift his arm, and meanwhile the bone is shaking, just sort of dangling. The body has gone away from it. Pieces of his lungs, of his liver, were coming out of his mouth. He was choking on his internal organs. I'd wrap my hand in a bandage, and put it in his mouth, take out all that stuff. It's impossible to talk about. It's impossible to write about, even to live through. It was mine, my love. They couldn't get a single pair of shoes to fit him. I buried him barefoot.

On the roof they gathered fuel and graphite from the reactor, shards of concrete and metal. It took about 20 to 30 seconds to fill a wheelbarrow, and then another 30 seconds to throw the garbage off the roof. So you can picture it. A lead vest, masks, the wheelbarrows, and insane speed.

SEIGEL: At the morgue they said, want to see what we'll dress him in? I do. They dressed him up in formal wear with a service cap. They couldn't get shoes on him because his feet had swelled up. They had to cut up the formal wear, too, because they couldn't get it on him, there wasn't a whole body to put it on. It was all wounds. The last two days in the hospital I'd lift his arm, and meanwhile the bone is shaking, just sort of dangling. The body has gone away from it. Pieces of his lungs, of his liver, were coming out of his mouth. He was choking on his internal organs. I'd wrap my hand in a bandage, and put it in his mouth, take out all that stuff. It's impossible to talk about. It's impossible to write about, even to live through. It was mine, my love. They couldn't get a single pair of shoes to fit him. I buried him barefoot.

On the roof they gathered fuel and graphite from the reactor, shards of concrete and metal. It took about 20 to 30 seconds to fill a wheelbarrow, and then another 30 seconds to throw the garbage off the roof. So you can picture it. A lead vest, masks, the wheelbarrows, and insane speed.

|

Unidentified Woman#3 (as Nadjiev DeBorakova): We're afraid of everything. We're afraid for our children and for our grandchildren who don't exist yet. They don't exist, and we're already afraid. People smile less, they sing less at holidays. The landscape changes, because instead of fields the forest rises up again, but the national character changes, too. Everyone is depressed. It's a feeling of doom. Chernobyl is a metaphor, a symbol. And it's changed our everyday life and our thinking.

Those readings taken from the book Voices From Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich. |